www.moonlandings.co.uk

Apollo 1 | Apollo 7 | Apollo 8 | Apollo 9 | Apollo 10 | Apollo 11 | Apollo 12 | Apollo 13 | Apollo 14 | Apollo 15 | Apollo 16 | Apollo 17 | Apollo 18 - Soyuz | Saturn V | Launch Complexes | Apollo Mission Summaries | Apollo Facts | Luna | Costs

Apollo 18 - Soyuz

Apollo 18 and Soyuz 19 Launched: 15 July 1975

Meeting in Space: 17 July 1975

Soyuz 19 Landed: 21 July 1975

Apollo 18 Splashed Down: 24 July 1975

Duration:

Apollo 18: 217 hours, 30 minutes

Soyuz 19: 143 hours, 31 minutes

Orbits: (Apollo 18) 136; (Soyuz 19) 96

Astronaut Crew:

Thomas P. Stafford

Vance D. Brand

Donald K 'Deke' Slayton

Cosmonaut Crew:

Alexei Leonov

Valeri Kubasov

This, the final flight of the Apollo spacecraft, was the first docking of spacecraft built by different nations and prestaged the era of cooperation between the Russians and the Americans that is now such an essential part of efforts to build a permanently occupied space station.

The American crew included three-flight veteran Thomas P. Stafford, rookie Vance Brand, and the last of the original seven Mercury astronauts to make it into orbit, Donald K 'Deke' Slayton, whose heart murmur had previously kept him grounded. The Soviet crew included the first space walker, Alexei Leonov, and rookie Valeri Kubasov.

While this mission is generally remembered as a political/public relations venture, it resulted in some major technological advancements necessitated by the requirement to dock the two extremely variant spacecraft, neither of which had been built for the purpose, together.

The two spacecraft were launched within seven and a half hours of one another, and, three hours after they docked two days later, the Astronauts and Cosmonauts met in the middle ahd shook hands in orbit, exchanged flags and gifts (including the seeds of trees that were later planted in each others' countries) and conversed haltingly with one another in each other's native tongues.

It would be six long years before another American astronaut would fly in space, this time aboard the reusable Space Shuttle. The Apollo era, an era of the greatest achievements in mankind's history, had ended.

Mission Details:

Mission Duration:

09 days, 07 hours, 28 minutes

15 - 24 July 1975

The Soyuz was launched just over seven hours prior to the launch of the Apollo CSM. Apollo then manoeuvered to rendezvous and dock 52 hours after the Soyuz launch. The Apollo and Soyuz crews conducted a variety of experiments over a two-day period. After separation, Apollo remained in space an additional 6 days. Soyuz returned to Earth approximately 43 hours after separation.

Mission Narrative:

The final flight of the Apollo programme was the first spaceflight in which spacecraft from different nations docked in space. In July 1975, a US Apollo spacecraft carrying a crew of three docked with a Russian Soyuz spacecraft with its crew of two. Apollo-Soyuz was the first international manned spaceflight. It was designed to test the compatibility of rendezvous and docking systems for American and Soviet spacecraft, to open the way for international space rescue as well as future joint manned flights. The existing American Apollo and Soviet Soyuz spacecraft were used. The Apollo spacecraft was nearly identical to the one that orbited the Moon and later carried astronauts to Skylab. The Soyuz craft was the primary Soviet spacecraft used for manned flight since its introduction in 1967. A docking module was designed and constructed by NASA to serve as an airlock and transfer corridor between the two craft.

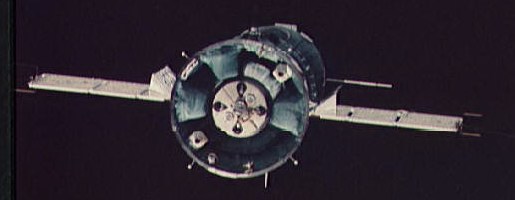

Soviet Soyuz spacecraft in orbit as seen from American Apollo spacecraft

For the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP), the United States used an Apollo Command and Service Module (CSM) modified to provide for experiments to be conducted during the mission, extra propellant tanks and the addition of controls and equipment related to the Docking Module. Launch was accomplished with a Saturn IB.

The Docking Module was designed jointly by the United States and Soviet Union, and built in the United States. Its purpose was to enable a docking between the dissimilar Soyuz spacecraft and the US Apollo. It was a three-metre long cylinder 1.5 metres in diameter, and in addition to serving as a docking device, also served as an airlock module between the different atmospheres of the two ships (the US ship with 100% oxygen at 260 millimeters of mercury; the Soyuz with a mixed oxygen-nitrogen atmosphere at 520 mm HG -lowered from its usual 760 mm Hg for this mission).

Prior to the conduct of ASTP, the astronauts and cosmonauts visited each other's space centres and became familiar with the spacecraft of the other country. The first visit was by the Russians to Johnson Space Center in July 1973, followed by a US visit to Moscow in November 1973. In late April and early May 1974, the Russian flight crews returned to Johnson Space Center, and the U.S. crews went to Moscow in June and July 1974. The Russian crew made a third trip to the United States in September 1973 and came for the fourth and last time in February 1975. The US crew visited the Soviet Union in late April and early May 1975 and became the first Americans to see the Russian launch facilities at Tyuratam on 28 April 1975.

Three simulation sessions were conducted between flight controllers and the ASTP crew in Houston and Moscow on 13, 15 and 18 May 1975 involving communications links between the two control centres, and fully occupied control centre facilities. A final simulation was conducted from 30 June - 1 July 1975. Additionally, in December 1974, the Russians made a human flight of the modified version of the Soyuz spaceship for system tests (Soyuz 16).

One of the most difficult problems to overcome was that of language differences. To alleviate this problem as much as possible, the Americans learned Russian and the Russians learned English. It was found that the best scenario was for the Russians to speak English and for the Americans to speak Russian.

Soyuz Launch: Soyuz 19, carrying cosmonauts Aleksey A Leonov and Valery N Kubasov, was launched into sunny skies from Baykonur Cosmodrome at 17:20 local time (08:20 EDT) 15 July 1975. The spacecraft entered orbit with a 221.9 km apogee, 186.3 km perigee, 88.5 min period, and 51.8 inclination.

Foreign correspondents, barred from the launch site, watched the launch on colour TV sets in a Moscow press centre. The first Soviet launch to be televised live, it was transmitted to viewers throughout the Soviet Union, the US and eastern and western Europe. President Ford watched from a US State Dept. auditorium with Soviet Ambassador to the US, Anatoly P Dobrynin and NASA Administrator James C Fletcher, before Dr. Fletcher and Ambassador Dobrynin flew to Kennedy Space Center to watch the Apollo launch.

On the third orbit the Soyuz 19 crew established contact with US mission control in Houston, putting into operation the global Moscow and Houston Soyuz-Apollo communications system. On the fifth orbit the cosmonauts made the first of two manoeuvers to place Soyuz 19 into a circular docking orbit. New orbital parameters were 231.7 km apogee and 192.4 km perigee. The spacecraft was spin-stabilised at 3 per sec with all systems operating normally.

Apollo Launch: At 15:50 EDT 15 July 1975, 7 hr 30 min after the Soyuz launch, a Saturn IB flawlessly lifted the Apollo spacecraft from Kennedy Space Center's launch complex 39, carrying Apollo commander Thomas P Stafford, command-module pilot Vance D Brand, and docking-module pilot Donald K Slayton. The spacecraft entered orbit with a 173.3 km apogee, 154.7 km perigee, 87.6 min period, and 51.8 inclination. The spacecraft's launch-vehicle adapter was jettisoned at 9 hr 4 min ground elapsed time (09:04 GET, counted from the Soyuz 19 launch) and the crew manoeuvered Apollo 18 to dock with the adapter and extract the docking module. These events were videotaped and transmitted to earth later via ATS 6 (NASA's Applications Technology Satellite launched 30 May 1974). A manoeuver 2 hr later at 19:35 circularised the orbit at 172 km. The Saturn S-IVB stage was deorbited into the Pacific Ocean 1 hr 30 min later.

A second Soyuz 19 circularisation burn of 18.5 sec at 08:43 EDT 16 July placed that spacecraft in a circular orbit of 229 km, with all systems functioning normally.

Rendezvous and Docking: A series of Apollo manoeuvers, with the final braking manoeuver at 08:51 EDT 17 July, put the Apollo spacecraft in a 229.4 km circular orbit matching the orbit of Soyuz 19. A few minutes later Brand reported "We've got Soyuz in the sextant" Voice contact was made soon after. "Hello. Soyuz, Apollo" Stafford said in Russian. Kubasov replied in English "Hello everybody. Hi to you, Tom and Deke. Hello there, Vance"

All communications among the five crew members during the mission were made in the language of the listener, with the Americans speaking Russian to the Soviet crew and the Soviet crew speaking English to the Americans. Contact of the two spacecraft, 51 hr, 49 min, into the mission (12:09 17 July) was transmitted live on TV to the earth, and Stafford commented "We have succeeded. Everything is excellent" "Soyuz and Apollo are shaking hands now" the cosmonauts answered. Hard docking was completed over the Atlantic Ocean at 12:12, 6 min earlier than the prelaunch flight plan watched by millions of TV viewers worldwide. "Perfect. Beautiful. Well done, Tom. It was a good show. We're looking forward to shaking hands with you in board [sic] Soyuz" Leonov said. Tass later reported that Kubasov told Moscow ground controllers that "we felt a slight jolt at the moment of docking" but that all went according to plan.

Joint Activities: At 15:17 hatch 3 opened; Apollo commander Stafford and Soyuz commander Leonov shook hands 2 min later. "Glad to see you" Stafford told Leonov in Russian. "Glad to see you. Very, very happy to see you" Leonov responded in English. "This is Soyuz and the United States" Slayton told TV viewers around the world. Both Soviet Communist Party General Secretary Leonid I Brezhnev and President Ford congratulated the crews and expressed their confidence in the success of the mission. Stafford then presented Leonov with "five flags for your government and the people of the Soviet Union" with the wish that "our joint work in space serves for the benefit of all countries and peoples on the Earth." Leonov presented the US crew with Soviet flags and plaques. The men signed international certificates and exchanged other commemorative items. After nearly 4 hrs of joint activities, including a meal aboard the Soyuz, the Americans returned to the Apollo and the hatch was closed at 18:51.

Soviet Soyuz spacecraft contrasted against a black-sky background

Soviet Soyuz spacecraft contrasted against a black-sky backgroundAn integrity check of the hatches indicated an atmospheric leak on the Soviet side. Ground controllers later attributed the indication to temperature changes in the sealed docking module that were detected by the sensitive Soviet instrumentation. Future integrity checks of the hatches would be more rigorous, however.

Following a sleep period, the crews prepared for another day of joint activity. Kubasov described the mission to Soviet TV viewers while the rest of the crews performed experiments in their respective spacecraft. At 05:05 18 July 1975 Brand entered the Soviet spacecraft; Leonov joined Stafford and Slayton in Apollo, greeting them with "Howdy partner." Kubasov gave American TV viewers a tour of his Soyuz, and Stafford followed with a tour of the Apollo. Then both Kubasov and Brand videotaped scientific demonstrations for transmission to earth later. Kubasov and Brand ate lunch in the Soyuz while Leonov ate with Stafford and Slayton in Apollo.

During a third transfer, Stafford and Leonov went into the Soyuz and Kubasov and Brand joined Slayton in Apollo. Brand gave Soviet viewers a Russian-language tour of the eastern US as seen from space. Further speeches and exchanges of commemorative items were made for both US and Soviet viewers before the final handshakes at 16:49 EDT 18 July when the crews returned to their respective spacecraft. The hatches were closed after Brand told Leonov and Kubasov "We wish you the host of success. I'm sure that we've opened up a new era in history. Our next meeting will be on the ground." Total time for all transfers and joint activities was 19 hr 55 min. Stafford had spent 7 hr 10 min aboard Soyuz; Brand, 6 hr 30 min; Slayton, 1 hr 35 min. Leonov spent 5 hr 43 min in the Apollo, Kubasov 4 hr 57 min. During nearly 2 days of joint activities, the five men carried out five joint experiments.

Undocking and Separation: The Apollo and Soyuz spacecraft undocked at 95:42 GET (08:02 EDT 19 July 1975). While the spacecraft were in station-keeping mode, the crews photographed them and the docking apparatus, transmitting the pictures live on TV to earth. The Apollo spacecraft then served as an occulting disc, blocking the sun from the Soyuz and simulating a solar eclipse the first man-made eclipse. Leonov and Kubasov photographed the solar corona as the Apollo backed away from the Soyuz and toward the sun. The two spacecraft then redocked at 08:34 EDT with the Apollo manoeuvering and the Soyuz docking system active while good quality TV was transmitted to earth. The second docking was not as smooth as the first because a slight misalignment of the two spacecraft caused both to pitch excessively at contact.

Final undocking also with the Soyuz active went smoothly and was completed at 11:26 EDT. As the spacecraft separated, the two crews performed the ultraviolet atmospheric absorption experiment, making unsuccessful data measurements at 150 m and then moving to a distance of 500 and 1,000 m, where data were successfully collected. The Apollo manoeuvered to within 50 m of Soyuz and took intensive still photography of the Soyuz. Separation maneuvers to put the two spacecraft on separate trajectories began at 14:42 with a reaction-control system burn. With the manoeuvers completed, Leonov told the Apollo crew "Thank you very much for your very big job....It was a very good show." Brand answered "Thank you, also. This was a very good job."

Soyuz Orbit and Landing: Soyuz 19 remained in orbit for nearly 30 hrs after the undocking. The cosmonauts conducted biological experiments with micro-organisms and zone-forming fungi. At 02:39 EDT 21 July the Soyuz crew closed hatch 5 between their orbital vehicle and descent module and began depressurizing the orbital module. Braking burns of the descent engines began at 06:06 when the spacecraft was 772 km from Apollo. The 194.9 sec burn slowed the spacecraft to 120 km/sec. After another burn to stabilise the spacecraft, the orbital and descent modules separated over Central Africa.

While Soviet viewers watched the first landing of a Soviet spacecraft televised in real time, the main parachute deployed at 7 km and jettisoned before the soft-landing engines fired. Soyuz 19 landed about 11 km from the target point northeast of Baykonur Cosmodrome at 06:51EDT 21 July after a 142 hr 31 min mission. The rescue helicopter approached the capsule immediately and specialists opened hatch 5. Kubasov stepped out waving to rescue-team members, followed by Leonov; both cosmonauts in apparent good health and spirits. The cosmonauts returned to Baykonur for medical checks and debriefings.

Apollo Postdocking Orbital Activities: Apollo remained in orbit while its crew continued US science experiments begun during predocking. Searching for extreme ultraviolet radiation, the ASTP crew marked the birth of a new branch of astronomy when they found, for the first time, extreme ultraviolet sources outside the solar system; some scientists had believed that such sources could never be found. One of the newly discovered sources turned out to be the hottest known white dwarf star. The Apollo detector also revealed the existence of the first pulsar discovered outside the Milky Way. About 200 000 light years from Earth's galaxy, in the Small Magellanic Cloud, it was the most luminous pulsar known to astronomers, 10 times brighter than any discovered up to that point. After repairing some malfunctioning equipment, the astronauts mapped x-ray sources throughout the Milky Way.

The crew completed nearly all the 110 earth-observation tasks assigned. Coordinated investigations had been made simultaneously by six groups of scientists on the ground, on ships at sea and in aircraft. The astronauts looked at ocean currents, ocean pollution, desert geography, shoreline erosion, volcanoes, iceberg movements and vegetation patterns.

On 23 July the command-module tunnel was vented and the crew put on spacesuits to jettison the docking module. The command and service module unlocked from the DM at 15:43 EDT, and a 1 sec engine firing put the CSM into a higher orbit (232.2 km apogee, 219.0 km perigee) so that the DM could move ahead. A second manoeuver put the CSM in a 223.2 km by 219.0 km orbit. Deorbit began at 16:38. The command module and service module separated, the drogue and main parachutes deployed normally and the Apollo splashed down at 224:58 GET (17:18 EDT 24 July) in the Pacific Ocean 163W and 22N, 500 km west of Hawaii. This was the last ocean landing planned for US human space flights; future flights on the Space Shuttle would be wheeled touchdowns at land bases.

The CM landed in "stable 2" position (upside down 7.4) km from the prime recovery ship, USS. New Orleans. After swimmers from the rescue helicopter righted the spacecraft and attached a flotation collar, the Apollo was lifted by crane on to the deck of the recovery ship and Stafford, Brand and Slayton stepped out to the cheers of the ship's crew. President Ford telephoned congratulations. During the welcome, the crew was evidently experiencing eye and lung discomfort; subsequent conversations and spacecraft data revealed that, during reentry, the earth landing system had failed to jettison the apex cover and drogues as scheduled and had to be fired manually, without first disabling the reaction-control system thrusters. With the CM oscillating, the thrusters began firing rapidly to compensate, and combustion products including a small amount of nitrogen tetroxide entered through the cabin-pressure relief valves. As soon as the RCS system had been disabled, fresh air was once again drawn into the cabin. The crew members told flight officials that they had put on oxygen masks once the spacecraft had landed, and then activated the postlanding vent system.

Because of the crew's discomfort, further shipboard ceremonies were cancelled and the crew were sent to sick bay and then to Tripler Hospital in Hawaii for observation until 8 August 1975.

The Apollo-Soyuz mission generated a notable volume of useful scientific data both from on-board experiments and from photography. Experiment MA-136, under the direction of Farouk El-Baz, was rather more elaborate than previous 70mm photography. In particular, it involved the astronauts more in making judgmental selections of targets for visual observation, drawing upon the Apollo lunar experiences which had further demonstrated the value of the human eye. There was also a substantial program of ground (and water) truth data collection. Because of the high latitude of the Soviet launch site, the ASTP mission involved a high inclination, 51.8, orbit that broadened the scope of regional coverage.

During the mission, some 2000 pictures were taken, about 750 of these of good quality (e.g., not cloud-obscured). Objections were diverse, covering geology, oceanography and meteorology. A characteristic scene is this view of part of southwest Africa in Angola, where unique drainage patterns are controlled by broad, partially revegetated dune fields

Conclusion:

Primary ASTP mission objectives were to evaluate the docking and undocking of an Apollo spacecraft with a Soyuz, and determine the adequacy of the onboard orientation lights and docking target; evaluate the ability of astronauts and cosmonauts to make inter-vehicular crew transfers and the ability of spacecraft systems to support the transfers: evaluate the Apollo's capability of maintaining attitude-hold control of the docked vehicles and performing attitude manoeuvers; measure quantitatively the effect of weightlessness on the crews' height and lower limb volume, according to length of exposure to zero-g; and obtain relay and direct synchronous-satellite navigation tracking data to determine their accuracy for application to Space Shuttle navigation-system design. The objectives were successfully completed, and the mission was judged successful on 15 August 1975 (More information)